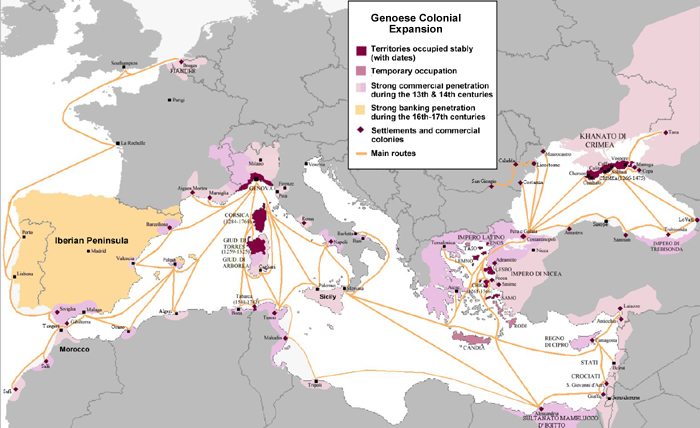

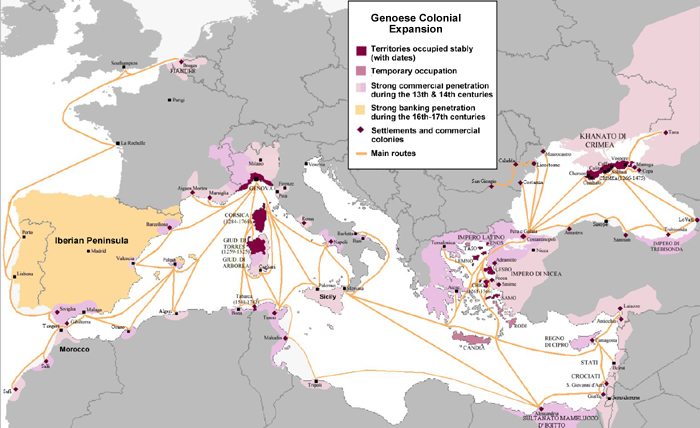

Genoese Sphere of Influence, 13th - 17th Centuries

Note: Atlantic Archipelagos and Americas not shown

Trade profit was calculated based on freight charges, for freight carried back to Genoa

from all overseas ports except Constantinople and Caffe (where the Genoese were exempt

from duty charges, per the 1261 Treaty of Nymphaeum). Charges were mostly predicated

on how much duty the ship would have to pay on its cargo before it could leave the

dock, but there were other considerations:

The weight of the cargo was measured by an ideal unit known as the milarium librarum Janue (1,000 Genoese pounds). In fact, carrying 1,000 pounds Genoese qualified the businessman as a merchant. Smaller units of measure were also used, such as the centarium (100 Genoese pounds). One must bear in mind that standard units of measurement were different in different places, and this required steps to equate measures in different ports. For example, the milarium was different in Constantinople, in the Black Sea, in Tunis, and in Acre (Syria). The practice of the Genoese was based upon Rhodian Sea Law, and was similar to the Sea Law of Barcelona.

Cargo was loaded at the expense of ship owners. Merchants forbade carrying cargo between decks during a trip. During the 14th century, marks were made on the hulls of ships to indicate the maximum level to which goods could be loaded. If a ship owner violated the law, freight rates were increased by 50%. Accounting records were kept by ship scribes (notaries) who watched the weighing, kept records, computed interest rates, calculated exchange rates between different currencies, calculated depreciation, and calculated the terms of accomendatio. Notarial records were called cartularium.

Since credit and letters of exchange were not yet widely used during this time period (1220-1260), merchants also had to take chests of money (gold or silver) to do business, thus bringing up questions of insurance. Such chests of money were also charged a duty. For the trade in the Levant, money was paid in bezants. Sometimes milarium biscanciorum argenti (silver bars) were used.1

Ships sailing from Genoa to the Levant were convoyed beyond Sicily by government galleys.

Genoese trading fortresses in the Crimea were under the supervision of the "Officium Gazariae". The "Officium Gazariae" or Imperium Gazariae, was named after the Khazar empire that existed prior to the Golden Horde, and may be viewed as Genoa's "Colonial Office".2 These Genoese trading fortresses included a diverse population, including Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Karaites, and Muslems (Tatars). Latin, Greek and Cuman (Tatar) were the official languages.

Financial records or treasurer's records were called "massarie" and were maintained by officals with the same name. All decisions were made by the consul and a council of elders or ancients composed of eight members, plus two massarii (treasurers) who controlled the city seal. The consul shared authority with the General Syndics (four elected magistrates that acted as a jury). The board of Syndics adjudicated all public communal events.

An "officium monetae" or mint was composed of four people; this unit was in charge of the mint's seal and oversaw the treasury books and tax collection. Construction was overseen by an officium provisionis. Issues of maritime trade were dealt with by an officium mercantie, subject to either the Officium Gazariae, or the compounded Genoese laws regulating trade. Provisions were regulated by an officium victualium during emergencies, such as sieges.

The counsul appointed non-elected officials such as the ministerialis (to regulate markets), cavalerius (director of the police), a captain to direct arguxii (auxilliary cavalry police), and a captain of the burgs (suburbs). There were city gate guards, stipendarii (mercenary soldiers), socii (slave soldiers), secretaries, a notary, and an engineer in charge of the water supply (in case of siege).

The slave trade was subject to regulation by Saint Antony's officium, and the slave merchants were allowed to participate in international trade (in the Black Sea, to the Mediterranean and the lands associated with these seas, including Syria, Palestine, Cyprus, Ionian Islands, Baleric Islands, North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, the coasts of France and Iberia). While mercatores could engage in international trade with any products, venditors were restricted to the Black Sea (not allowed to engage in international trade), and only allowed to trade in one product.

Trade on the seas typically used galleys, with slave rowers. Ship's company typically were armed with crossbows, trebuchets, and swords.

Currency was composed of gold and silver bars measured in summos, with a saggiatore (assayer) to determine weights and purity. Trade goods included slaves, grain, pannos bagadellinos (oriental rugs), cloth (lienço ginovisco, cañmazo), mastic, cotton, clothing, wool, alum, orchil weed, spices, coral, precious jewels, sugar and money (carried aboard ship).

As time passed, other institutions developed such as sarabaria (munitions depots), darsena (docks), cecca (mints), fabrica moenium (stone quarries), various artisans such as weavers, potters, glass blowers, fishermen, etc. Most traders spoke several languages including Cuman (Tatar), Latin, Uigar, and Arabic. Schools were created to teach classical languages (Greek, Armenian, Cuman) and the study of literature.

Maritime trade was developed based on societas and accomendatios to raise capital,3 using factors to establish "factories" with fonduks (fond'iqs) or warehouses, first in Europe (Iberia, North Africa, Sardinia, Sicily, etc.), then in the Levant (Byzantium, Palestine and Syria, Cyprus, the Black Sea etc.), then in the Atlantic archipelagos (Canaries, Madeiras, Azores)4. After this, accomendatios were replaced by compañías (vera societas), used primarily by the Genoese who were involved in Carrera de Indias (transatlantic slave trade), trading black African slaves to work in plantations and mines, in exchange for agricultural products such as sugar, or gold, silver, precious stones, etc. Thus the Genoese gave birth to modern slavery on an international scale.

| Accomendatio |

A commercial agreement between two partners, the accomendator (or

the investor) and the accomendatorius (or factor). The accomendator

provides all the capital invested and remains in Genoa. The accomendatorius

provides no capital, but travels, carrying the total investment, paying his

expenses from the capital. Upon return to Genoa, and three forths of the proceeds belong

to the accomendator, one forth of the proceeds are allocated to the

accomendatorius. Initially, the factor travels 3 to 4 months, but by 1200 AD,

factors might not be living in Genoa for years. Variants evolved:

|

| Carrera de Indias | Refers to trade in African black slaves, paid for with sugar, cattle hides, or other agricultural products. |

| Compañía |

A non-family partnership of unlimited liability, in which the "rule of three" applies:

"A typical division would be among three individuals: two capitalists, either members

of the lower nobility or merchants, and a shipmaster. Accomendatios evolved into

compañías,and were used primarily by the Genoese in the Carribbean,

especially in the carrerea de Indias. Compañías were based on the real partnership

rules of the Middle Ages (vera societas). (See Pike, "Enterprise and Adventure",

pp. 68-69, footnote 66; p. 81, footnote 114 and Pike, "Aristocrats and Travelers",

p. 31.)

Hernán Cortés used Genoese factors to import black slaves, who were then used on his sugar plantation at Tuxtla (just south of Ciudad Mexico). Cortés paid the factors in sugar. See Carrera de Indias. |

| Casa de Contratación | Government bureau that licensed and supervised all ships, merchants, passengers, ship's goods, crews, and equipment, passing to and from the Indies, enforcing all laws and ordinances relating thereto. (Foreigners, moriscos, conversos, Jews, Moslems, Lutherans, were not allowed to book passage.) The Casa also "received and cared for royal treasure remitted from the New World and collected the avería or convoy tax and customs and other duties. During the first half of the sixteenth century it gradually became a training school for navigators, makers of maps and devisers of nautical instruments. [The Casa also served as] a court of law with jurisdiction over all cases incidental to American trade." (See Pike, "Enterprise and Adventure", p. 152, note 43.) |

| Comperarum | An association of Genoese investors who purchased loca or shares, in the company. |

| Compere | Companies that administered municipal finances in Genoa. |

| Fondac, Fond'iq, Fonduk, Funduk | Warehouse. |

| Imperium Gazariae | See Officium Gazariae. |

| Mahona or societas compararum |

Colonial Genoese company (fourteenth century) that carried out long-distance or international

trade with Crimean Genoese colonies and colonies in the Levant (Aegean Sea, Ionian Sea, Balkans

in Greece, Cypress, Corsica, Syria and Palestine). Mahonas were more than companies with

shareholders (investors); they could also include fiefs granted to 'Captains'(or regidors). The

fiefs were usually granted in perpetuity (inherited under primogeniture). The land could be

subenfifed. In addition to this, the use of mills (water- or wind-powered); later,

atafona or trapiches (powered by animals) and specialized equipment such as pipes for irrigation, was a

monopoly of the captian (or regidor). The captain may also have had a monopoly on bakeries.

Sometimes there were limitations to the power of the seigneur, to show that the seigneur was still subject (under vassage) to the power of the King or Emperor. For example, the seignur could not try cases of capital punishment. Examples: Lanzaretta Malocello (Canary Archipelago), Alonso de Lugo (Canary Islands), and the father-in-law of Christopher Columbus. 5 Mahonas were subject to the purview of the Bank of St. George. Note: The Genoese had a mahona that dealt with Chios (in the Ionian Sea). Later on the Dutch, English and French constructed East India Companies and West India Companies that acted in this fashion. |

| Officium Gazaire, Officium Gazariae | Genoa's "colonial office" in the Crimea. The "Officium Gazariae" or Imperium Gazariae, was named after the Khazar empire that existed prior to the Golden Horde. 6 The Officium Gazariae was first "house of trade" to control colonial trade. |

| Societas maris |

A commercial agreement between two partners, the socius stans (principal or investor)

and the socius tractans or portitor or factor. The socius stans

provided two thirds of the capital and remained in Genoa. The socius tractans provided

one third of the capital, and travelled to the Levant, North Africa, or Spain, etc. The profits

from trade were sent to Genoa, and upon the factor's return to Genoa, profits were half to

the socius stans, the remaining half to the socius tractans. Variants evolved:

as follows:

|

| Vera societas | See compañía. |

| Alum | Found in Phocacian mines; used to dye cloth, typically wool |

| Atafona | Trapiche (typically horses or oxen) sugar press |

| Cabin | Thalamum, paradisus, camera |

| Camera | Merchants used decks for cooking, bedding, servants, etc. Space on the decks was allocated by share. For example: one forth share, then one forth deck space. A camera (cabin) could be constructed for the merchant. Merchants often set limits to the number of people, horses, mules and falcons allowed aboard. |

| Castellum | For wealthy merchants or passengers. Sometimes there was a supercastellum. |

| Conductus | A mariner's wages. |

| Contracts/law |

Initially (12th century) there were no written contracts. All was done by verbal

agreements based upon custom, mutual trust and reputation, maybe before witnesses,

on a street or wharf. By the 13th century, written contracts, but only for the

largest merchants or shipowners. By the 14th century, all contracts are written.

Law developed following trade practices. Merchants found shipowners, formulated a

contract with a notary in common language, which was then put into formal Latin,

called a "de naulo" with three parts: (obligations of ship-owners; obligations of

merchants; pledges of payment and penalties if the contract was not fulfilled).

|

| Equipment |

Equipment used aboard ships included:

|

| Facta ad narem | Table of relative weights to bulk. |

| Facta prima calica | First public sale of wares (if payments were deferred, merchants could pay after the first public sale). |

| Ca˝mazo | canvas, sometimes called vitry |

| foenus nauticum | Sea loan (typically at 20% to 50% in interest). |

| Frangoumates | Term used in Jerusalem for freed slaves |

|

Galleys

(galea, galeotus, sagitta) |

Used oars, sometimes had 2 masts |

| Goods of trade | Trade goods included slaves (a major "product" - mostly from Slavic sources), cloth (lienšo ginovisco, ca˝mazo), cotton, clothing, wool, alum, mastic, orchil weed, hemp, grain, manufactured wooden ware (especially for Tunis), heavy and bulky materials (copper, lead, tin, iron, canvas), wine (mostly to North African Moslem ports as it was against religious law to drink wine: measured at 13 mezzarole per milarium librarum Janue), lacquer, pepper, saffron, pannos bagadellinos (oriental rugs), sugar, and coral. |

| Griffin | Half-blood slave. Used in Famagusta, Cyprus 1299-1301, to refer to the offspring of Slavic (white) slaves who were employed at sugar plantations at Genoese and Venetian colonies. The use of this term suggests the beginnings of a caste system based on status (slave or free man), pre-dating the use of caste in the New World, to indicate mixed "race" (color) status.7 |

| Jarra | Jar |

| Lienço Ginovisco | Genoese linen |

| Loca | Vessel ownership in shares (often 16 to 70). The number of loca was equal to the number of mariners. |

| Magister axie | Master shipbuilder. |

| Mastic | Adhesive made from tree sap, used to seal ship joints |

| Masts | Forward mast: arbor de prora or de proda; Second heavier and taller: arbor medio |

| Mezzarole | Wine measured in "mezzarole", at 13 mezzarole to one milarium librarum Janue. (Moslem countries — where wine-drinking was not permitted — nevertheless imported wine.) |

| Naulum | Freight. |

| Orchil weed | A lichen used for dyeing. |

| Orlum | Rail or upper deck, 45 to 54 inches high from bow to stern, used as a barricade during attack. |

| Pannos bagadellinos | Oriental rugs. |

| Patronus | Several investors pooled shares, and chose a lead investor called the "patronus". Mates also had shares, called "nauclerius". Salary was called "naucleriam". |

| Pontibus levatoribus | Draw bridge or gang plank used for embarkation/debarkation. |

| Res subtilis | Chests of pepper, saffron and other spices. 8 |

| Risicum | Risk of loss. |

| Sailing ships (Navis or bucius) | Crusader and pilgrim ship passengers. |

| Sporte | Basket. |

| Stiva | Hold. |

| Timones | Two heavy lateral rudders on the sides of a ship, near the stern. |

| Trade (three classes) |

At this time, Naval navigation used cartographic maps called portolans.

The compass was not introduced until 1325.

|

| Weights | Milarium (1000) librarum Janue: 1000 pounds, Genoese weight. Note: centanarium was 100 pounds, Genoese weight. A "milarium" weighed differently in Constantinople, Syria (Acre), Tunis, Black Sea ports, etc. |

Sailing ships were originally used primarily to transport crusaders and pilgrims. As traffic in crusaders and pilgrims diminished, galleys were favored in the trade with the Levant and Flanders: galleys were faster, cheaper, and more easily defended.

For a complete list of the references used to create this section of the Esther M. Lederberg Memorial Website, click here.